Disputably, there is greater value and meaning in youth culture that is authentically produced as opposed to manufactured culture. Synthetically produced aspects of music (which Jake Bugg states he is “championing against”- NME 2012), akin to the X-factor talent shows, boy bands, girl groups for example, may lack artistic credibility due to not writing their own material (Stahl, 2002; Huffington Post, 2011). They are usually perceived as products solely for financial gain in a culture of instant gratification (The Guardian, 2011; Independent, 2012). This is juxtaposed with the authentic; concerning itself with the truthfulness of origins, sincerity and intentions (Dutton, 2003). Arguments regarding authenticity have arisen since the dawns of popular music, with folk-blues musician Leadbelly being marketed by his prior criminal convictions to sell records (Filene, 2000). Discussions have continued, keeping it a forever unresolved topic.

Subcultures are distinguished in terms of what they are and are not (Force, 2009). Amongst many genres (Rose, 1994; McLeod, 1999), punk rock is associated with being a sincere representation of youth culture that is habitually in opposition to mainstream culture. Its aggression in terms of both image and music, confrontational attitude and shock factor challenges the notions of conforming to an ideal appearance and hegemony (Hebdige, 1979). Despite this, punk is not entirely free from criticisms of inauthenticity, as the mainstream has commoditized aspects of the subculture. Concepts of what is and isn’t “punk” are continuously discussed (Stereogum, 2014), as well as the concept that “punk is dead” entirely (Clark, 2003), or if it has evolved into a notion where the ethos is still relevant (Fact, 2013). Arguments have arisen from if punk is a constructive subculture that possesses great value and meaning or if it as much of a commercial force as mainstream manufactured culture.

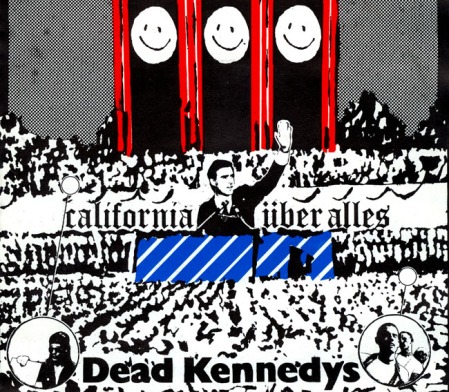

Commonly, the consensus of what punk subculture “is” revolves around punk rock music, the style of attire and the attitude that punks express. Hebdige (1979) states that these factors are a reflective image of Britain’s post-war decay, where boredom and decline are represented in young people’s lives through simple, aggressive music, obscure and deliberately shocking clothing and a care free attitude of nihilism (Marcus, 1989). This is pre-eminently exemplified in the Dead Kennedy’s song, ‘California Uber Alles’ (1980; Kennedy, 1990) a satirical piece that constructs a fascist-hippie utopia from the perspective of Governor Jerry Brown. Apparel worn by punks shows a stylized presentation of themselves (Force, 2009) and is used to identify symbolic resistance, show disaffiliation from the mainstream culture and form a collective identity of solidarity and belonging to the subculture (LeBlanc, 1990). Punks appropriate signs and symbols to form their fashionable “anti-fashion” (Moore, 2004) such as wearing safety pins, Nazi swastikas, ripped clothes, items of merchandise of punk groups and bondage gear. Adopting items such as sexual paraphernalia and fascist imagery is to deliberately shock and offend (Hebdige, 1979). The Sex Pistols appropriated symbols of the Monarchy in the lead up to the Queen’s diamond jubilee. By using imagery associated with conservative Britain and the ruling classes such as the Union Jack and a defaced Queen Elizabeth, they attempted to show the ugly side of “the sick man of Europe” in the late 70s, a country steeped in financial turmoil and unemployment. An image that the Jubilee was trying to avert (Savage, 1979).

In Force’s (2009) observations, members of the subculture presented themselves as “being punk” through clothing and knowledge of punk culture and history. Owning a rare, esoteric record shows a legitimacy of awareness and confirms their identity, conforming to Goffman’s theory (1959) that objects convey meaning of oneself and Bennett’s (2000), which states that collective cultural meanings are inscribed in objects that allow for identity construction. Punk is a taste culture that features hierarchies of “hipness” so acting on this performance shows perceived authenticity (Thornton, 1995).

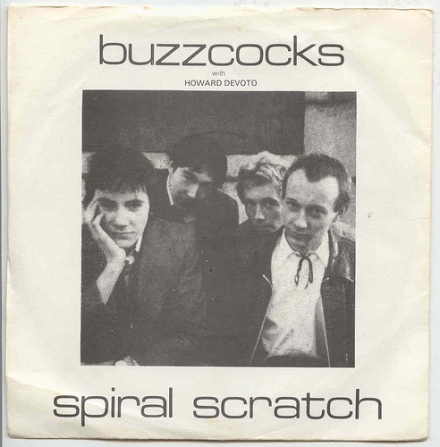

Through observing punk subculture, it is possible to understand a value in its ethos. Ideologies such as gender equality and gender issues (Against Me!, 2014), gay rights (Tom Robinson Band, 1979), racial equality, class issues and pro-health have been promoted through punk rock music. It is easy to set up a group, play the music and distribute thanks to punks anti-virtuoso and “do it yourself” stance (Hesmondglaph, 1998; Dale 2009). Punk music is a reaction to the upper-middle class and the virtuosity of progressive rock (Moore, 2007; Buzzcocks, 1977) thus allowing individuals the opportunity to get their message heard (Reynolds, 2006).

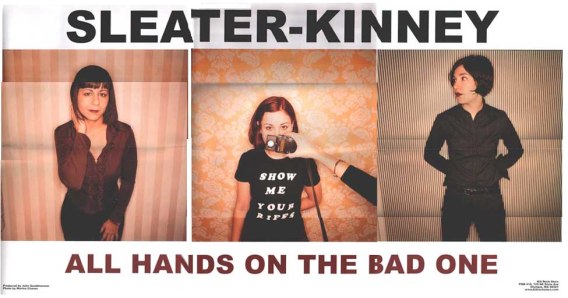

Young women were given a voice by the ‘riot grrrl’ underground movement, promoting feminist ideology in a genre known for its aggressive machoism (Marcus, 2010). They circulated their music and message of gay rights (Goldthorpe, 1992), gender empowerment and equality through independent labels (such as Kill Rock Stars), leaflets known as zines and activist events such as Rock for Choice (Leanord, 1997). However, some argue that mainstream culture can feature positive aspects of feminism, as the Spice Girls “Girl Power” rhetoric appealed, empowered and encouraged solidarity in young girls (Gonick, 2006).

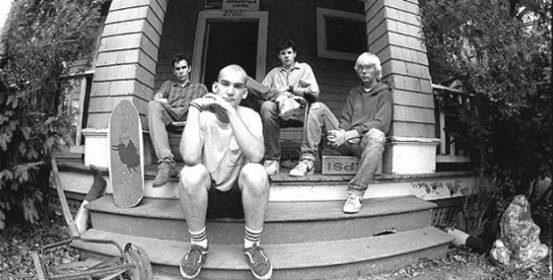

Similarly, the straight edge mind-set was brought to attention through zines and DIY punk music distributed through an independent label (Williams, 2006). The term, most notably appreciated and stemmed from Minor Threat’s ‘Straight Edge’ (1981), refers to a lifestyle of abstaining from consuming alcohol, tobacco and other recreational drugs. Independent label Dischord specializes in affordable, DIY, local and straight edge music (Goshert, 2000; Dunn 2008).

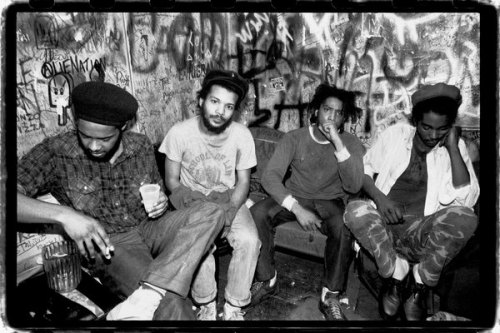

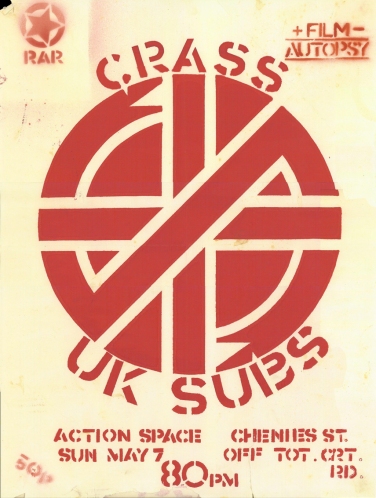

Racial equality was promoted in punk through events such as Rock Against Racism, featuring punk bands such as The Clash, Sham 69 and Buzzcocks (Goodyer, 2003). Furthermore, all-African American group Bad Brains promoted black awareness and liberation through their music which fused hardcore punk consciously with Rastafari roots-reggae (Moskowitz, 2006).

Subgenres such as Oi! and anarcho-punk intended issues regarding class exploitation and consciousness were stressed. Oi! attempted to bring together a collective working class culture of punks, skinheads and rudeboys who were pro workers’ rights and anti-youth unemployment (Robb, 2006). Anarcho-punk (where the music was just as extreme as its radical leftist sentiment), a genre spearheaded by Crass, was a reaction to the commercial. Their vocals would overshadow the music thus the message was the primary instrument on display (Rimbaud, 1998).

Belonging to the punk subculture allows for the individual to establish a network of underground media that expresses artistic sincerity and independence from the allegedly corrupting influence of commerce (Moore, 2004). It is a subculture where radical voices can be heard and spark influence. Women have been empowered through riot grrrl and thousands have become healthier due to the influence of straight edge, illustrating why authentic youth subcultures such as punk possess greater value and meaning than manufactured culture, which may never be as influential in a positive way.

Punk subculture isn’t free from judgements of the inauthentic and manufactured. Punk has its origins in middle class and art school backgrounds (Clarke, 1981), leading to conflicts internally from anarcho and Oi! fans. Redhead (1993) argues that youth subcultures such as punk suffer from in-authenticity and superficiality issues. McCracken (1998) states that acts of protest are formed through commodities that conform to a participation in a set of shared values and meanings; authenticity is based on subcultural capitol (Thornton, 1995). This can be seen in the punk “outfit” which ironically shows uniformity (Widdicombe, 1990; Force 2009). Identity of the subculture is constructed through comparison which provide members a sense of belonging in the social world (Tajfel, 1979). Muggleton (2008) argues that there are no original cultures, just hybridised forms of nostalgia. This can be observed by mainstream retailers selling commoditized punk attire, to those whom may have never heard the artists. (Bowe, 2010; Pitchfork, 2013). Even the “un-style” of grunge was capitalized by fashion (Clark, 2003). Aspects such as these indicate arguments that “punk is dead” due to its adoption by manufactured culture.

Ultimately, despite criticism and trivial commodification, punk is still a relevant subculture that possesses greater value and meaning comparably to manufactured culture. It may not be seen ostensibly, due to style mixing and eclecticism of contemporary taste (Polhenmus, 1997), as various scenes have stemmed from punk. (Bennett, 2006). Punks impact has spawned post-hardcore, folk punk and post-punk (Reynolds, 2006; Wagner, 2007), even genres such as thrash metal, indie rock and gothic rock are a result of punks splintering influence. This is all made more accessible to listen to, communicate, distribute and create thanks to technological advances and the Internet (Moran, 2011).

Punk can be used as a descriptor to show an anti-establishment ethos or attitude. Experimental hip-hop group Death Grips deliberately leaked their first album for major label Epic for free online, with responses from fans and music publications declaring this was “punk” (Noisey, 2013; Rolling Stone, 2012). Sleaford Mods offer a scathing view of contemporary Britain in a form of working class punk poetry (Fact, 2013) and “post-rock” group Godspeed You! Black Emperor’s radical views and shunning of the music press and industry led them to be named them “punks in the truest sense” (Guardian, 2012; Rumpus, 2014).

With a DIY ethic and “anyone can make it” attitude, punk subculture has enlightened many about positive movements regarding race, class, health, gender and homosexuality in a manner of social change. Punk continues to adapt, as shown in the definition of “what is punk?” changing and still relevantly targets social issues, as exemplified in Against Me!’s Transgender Dysphoria Blues (2014). Comparatively, manufactured culture is unfulfilled in this manner, so authentically produced youth cultures will continue to have control over meaning and value.

The question for this essay: Jake Bugg (NME, 17th November 2012) claimed that “it’s my job to keep that X-Factor shit off the top of the charts”. Critically assess the contention that there is greater value and meaning in youth culture that is authentically produced by young people as opposed to manufactured culture.

References/Footnotes:

Against Me! (2014). Transgender Dysphoria Blues.

Bassil, R. (2013). Are Death Grips the Only Punk Band We Have Left? Available: http://noisey.vice.com/en_uk/blog/are-death-grips-the-only-punk-band-we-have-left. Last accessed 17th December 2014.

Battan, C. (2013). Ian MacKaye Says Urban Outfitters Is Authorized to Sell Minor Threat Shirts. Available: http://pitchfork.com/news/51717-ian-mackaye-says-urban-outfitters-is-authorized-to-sell-minor-threat-shirts/. Last accessed 17th December 2014.

Bennett, A. (2000). Popular Music and Youth Culture: Music Identity and Place. 27. London, Macmillan.

Bennett, A. (2006). Punk’s Not Dead: The Continuing Significance of Punk Rock for An Older Generation of Fans. Sociology, 40(2), 219-235.

Blackman, S. (2005). Youth Subcultural Theory: A Critical Engagement with the Concept, Its Origins and Politics, From the Chicago School to Postmodernism. Journal of Youth Studies, 8(1), 1-20.

Bowe, B. (2010). The Ramones: American Punk Rock Band. Enslow Publishers, Inc.

Breihan, T. (2014). Joyce Manor Ignite Punk Scene Controversy With Anti-Stagediving Stance. Available: http://www.stereogum.com/1707809/joyce-manor-ignite-punk-controversy-with-anti-stagediving-stance/video/. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Buzzcocks. (1977). Boredom. Spiral Scratch.

Clark, D. (2003). The Death and Life of Punk, the Last Subculture. In David Muggleton and Rupert Weinzierl (eds.), The Post-Subcultures Reader. Oxford: Berg. 223-236.

Clarke, G. (1981). Defending Ski-Jumpers: A Critique of Theories of Youth Subcultures. Reproduced in S. Frith and A. Goodwin (eds.), 1990. On Record: Rock, Pop and the Written Word. London. Routledge

Cosslett, R. (2012). The Spice Girls Were My Gateway Drug To Feminism. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/dec/13/spice-girls-feminism-viva-forever. Last accessed 20th January 2015.

Costa, M. (2012). Godspeed You! Black Emperor: ‘You make music for the king and his court, or for the serfs outside the walls’. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/music/2012/oct/11/godspeed-you-black-emperor-interview. Last accessed 17th December 2014.

Dunn, K. C. (2008). Never Mind the Bollocks: The Punk Rock Politics of Global Communication. Review of International Studies, 34(1), 193-210.

Dutton, D (2003). “Authenticity in Art”. In Jerrold Levinson. The Oxford Handbook of Aesthetics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Filene, B. (2000). Creating the Cult of Authenticity. Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music. UNC Press Books. 47-76.

Force, W. R. (2009). Consumption Styles and the Fluid Complexity of Punk Authenticity. Symbolic Interaction, 32(4), 289-309.

Goldthorpe, J. (1992). Intoxicated Culture-Punk Symbolism and Punk Protest. Socialist Review, 22(2), 35-64.

Gonick, M. (2006). Between” Girl Power” And” Reviving Ophelia”: Constituting The Neoliberal Girl Subject. NWSA Journal, 18(2), 1-23.

Goodyer, I. (2003). Rock Against Racism: Multiculturalism and Political Mobilization, 1976–81. Immigrants & Minorities, 22(1), 44-62.

Goshert, J. C. (2000). “Punk” After the Pistols: American Music, Economics, and Politics in the 1980s and 1990s. Popular Music & Society, 24(1), 85-106.

Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The Meaning of Style. New York: Routledge.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (1998). Post-Punk’s Attempt to Democratize the Music Industry: The Success and Failure of Rough Trade. Popular Music, 16(3), 255–74.

Huffington Post (2011). Simon Cowell’s The X Factor Is Killing Music. Available: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/01/12/charlotte-church-simon-cowells-x-factor-is-killing-music_n_807929.html. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Kennedy, D. (1990). Frankenchrist Versus The State: The New Right, Rock Music And The Case Of Jello Biafra. The Journal of Popular Culture, 24(1), 131-148.

Kennedys, D. (1980). California Uber Alles. Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables.

Leblanc, L. (1999). Pretty in Punk: Girl’s Gender Resistance in a Boy’s Subculture. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Leonard, M. (1997). Feminism, ‘Subculture’, and Grrrl Power. Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender. Ed. Sheila Whitely, 230-255.

Marcus, G. (1989). Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Marcus, S. (2010). Girls to the Front: the True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. HarperCollins.

McCracken, G. (1988), Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities, Bloomington and Indianapolis. IN: Indiana University Press.

McLeod, K. (1999). Authenticity Within Hip‐Hop and Other Cultures Threatened With Assimilation. Journal of Communication, 49(4), 134-150.

Moore, R. (2004). Postmodernism and Punk Subculture: Cultures of Authenticity and Deconstruction. The Communication Review, 7(3), 305-327.

Moore, R. (2007). Friends Don’t Let Friends Listen to Corporate Rock Punk as a Field of Cultural Production. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 36(4), 438-474.

Moran, I. (2011). Punk: The Do-It-Yourself Subculture. Social Sciences Journal, 10(1), 58-65.

Moskowitz, D. (2006). Caribbean Popular Music. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.18–19.

New Musical Express. (2012). Jake Bugg: ‘I’m Keeping That X Factor Shit off the Top Spot’. Available: http://www.nme.com/news/jake-bugg/66756. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Pattinson, L. (2013). “The Song? Fuck Off”: Lo-Fi Punk Poets Sleaford Mods Big Up Wu-Tang And Savage The System. Available: http://www.factmag.com/2013/05/03/the-song-fuck-off-lo-fi-punk-poets-sleaford-mods-big-up-wu-tang-and-savage-the-system/2/. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Redhead, S. (1993). Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture, Aldershot Avebury Press, Aldershot.

Reynolds, S (2006). Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–1984. Faber and Faber.

Rimbaud, P. (1998), Shibboleth – My Revolting Life, San Francisco CA: AK Press.

Robb, J. (2006). Punk Rock: An Oral History, London: Elbury Press.

Rose, T. (1994). Black Noise: Rap Music And Black Culture In Contemporary America (Music Culture) Author: Tricia Rose, Publisher: Wesleyan.

Rubsam, R. (2014). The Rumpus Interview with Efrim Menuck. Available: http://therumpus.net/2014/04/the-rumpus-interview-with-efrim-menuck/. Last accessed 17th December 2014.

Sabbagh, D. (2011). Universal and Sony Music Plan ‘Instant Pop’ to Beat Piracy. Available: http://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jan/16/universal-sony-music-singles-release. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Savage, J. (1992). England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Stahl, M. (2002). Authentic boy bands on TV? Performers and Impresarios in The Monkees and Making the Band. Popular Music, 21(3), 307-329.

Sturges, F. (2012). Graham Coxon: All a Blur. Available: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/graham-coxon-all-a-blur-7765872.html. Last accessed 15th December 2014.

Tacopino, J. (2012). Death Grips Implode Punk and Rap Borders on New LP. Available: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/death-grips-implode-punk-and-rap-borders-on-new-lp-20120424. Last accessed 17th December 2014.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. (1979). An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 33(47), 74.

Thornton, S. (1995). Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Threat, M. (1981). Straight Edge. Minor Threat.

Tom Robinson Band. (1978). Glad to be Gay. Rising Free.

Wagner, C. & Stephan, E. (2007). Left of the Dial: An Introduction to Underground Rock, 1980-2000. Music Reference Services Quarterly, 9(4), 43-75.

Widdicombe, S. & Wooffitt, R. (1990). Being ‘Versus’ ‘Doing’ Punk: On Achieving Authenticity as a Member. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 9(4), 257-277.

Williams, P. (2006). Authentic Identities Straightedge Subculture, Music, and the Internet. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 35(2), 173-200.

Recent Comments